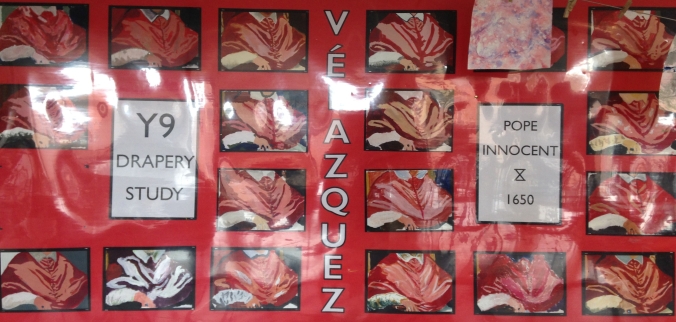

YEAR 9 DRAPERY STUDY

As part of my role, I am fortunate enough to have curriculum conversations with many exceptional colleagues who possess incredible expertise in, and passion for, their subject. One of the ongoing conversations I enjoy most is with the art teacher at Bedford Free School, whose thoughtful approach to curriculum design in art is impressive to say the least.

From our conversations I have managed to persuade her to allow me to blog about her art curriculum, mainly because I am sure other people will find it as fascinating as I have. What follows is drawn from her own notes and words about the thinking and decision making that went into her KS3 curriculum design, which I have merely edited.

RE-DESIGNING THE ART CURRICULUM AT BEDFORD FREE SCHOOL

Before discussing the curriculum, it is important to understand our art teacher’s position on art. At secondary school, she experienced a classical art education, with an emphasis on art history. During her foundation course she clashed with tutors because she admired Henry Moore, who wasn’t considered fashionable. She then went to one of the oldest art schools in the world, where teaching methods and an emphasis on traditional skills had barely changed since the early 1800s. This is what has influenced her as an artist, and she believes in the power of her art education, which stems from a tradition that prevailed for well over 500 years, and combines the development of practical skills with an understanding of the history of art.

When designing the art curriculum at Bedford Free School, she began by considering two areas:

- Knowledge and history (theory)

- Skills and application (practical)

Although both feed into each other, as we teach ‘Art’ and not ‘Art History’ the practical side took precedent in her decisions on what to teach.

INITIAL DECISION MAKING

What practical art do we want the students to learn?

What practical art should everybody be offered the opportunity to master?

What are the main areas of practical art?

From these questions, she came up with areas to focus practical art upon:

- Drawing

- Painting

- Sculpture

- Printmaking

The next question was, in what order should they be taught?

Logically, and historically, in art teaching, drawing is the absolute foundation of all art forms. It is the first and most important skill as it is the skill that underpins all others. This is why she came to the decision that the students should be taught drawing first. Painting is the next logical step: when most people thinks of art they think of great paintings by Picasso, Dali, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt.

Painting is split in to two areas: brush skill and techniques, and use of colour. Can (or should) you teach how to paint and hold a brush if you can’t use or control colour? No, so colour theory comes first, and using a medium that requires little emphasis on skill.

With regards to sculpture and painting, should students learn how to manipulate 3D forms before learning how to describe them adequately in 2D? Probably not, so sculpture must be last.

Even after developing some sense of focus and order, there were still many questions to consider. Where does printmaking fit? Should year 7 be entirely drawing, Y8 colour and painting and Y9 sculpture? Possibly, but that would have sectioned off each area too much, and ignored the interdependent nature of art: you can’t have one without the other; you can’t have painting without drawing.

These thoughts led to the first major decision slotting into place. There are three terms per year and three main interdependent practices. Each year at KS3 would follow the same basic pattern: term 1 drawing; term 2 colour and painting; term 3 sculpture.

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 | |

| Year 7 | Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture |

| Year 8 | Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture |

| Year 9 | Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture |

MORE DECISIONS

What subject to use to teach drawing?

What subject to teach painting?

What subject to teach sculpture?

Should all the drawing sections be the same subject, just getting more complex and relying on differentiation by outcome? If students draw a banana in year 7 then again in year 8 and yet again in year 9, they will obviously be better at it. What would progress look like across each year – from drawing to sculpture – if they are different themes/topics? And is this still missing the interconnectivity, interdisciplinary nature of the subject? Could you take one subject and use it for drawing, painting and sculpture? If you do that, what progress do you build in from year to year? In year 7 the subject needs to be basic, in year 8 slightly trickier and by year 9 should be very complex.

AND YET MORE BIG DECISIONS TO MAKE

What are the main subjects/ themes that link all areas of Art?

- Still life

- Portraiture

- Religion

- Literature/story telling

- Drapery

- Animals

- Landscapes

How do you choose 3 from the whole gamut of the history of humanity?

In the end, as far as our art curriculum is concerned, the decision as to which are the most important areas to know about has been made based on personal preference and professional experience and judgement. You can argue that they all are equally important, and this is what makes planning a cumulative curriculum so tricky.

Our art teacher’s decisions were:

- Still life for Y7, as these can be simplified into basic shapes, and easier to construct to good effect.

- Portraiture for Y8, which offers far more complex forms to decipher, and moving subject matter.

- Wanting to teach every aspect of art not covered by the above, she combined the remaining areas together into ‘History of western art’ which explain the development of art from the Greeks to now and everything in-between.

So now there was a very basic plan:

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 | |

| Year 7 | Still life | ||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture | |

| Year 8 | Portraiture | ||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture | |

| Year 9 | Art history | ||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | sculpture | |

Unlike most other subjects, the national curriculum guidelines for teaching art are almost non-existent. There is no requirement to teach particular movements, artists’ styles, or techniques. It is an almost completely teacher/school led choice. Whatever is taught however has to cover the ‘formal elements’:

- Line

- Shape

- Form

- Tone

- Texture

- Pattern

- Colour

Most of these can be addressed through the areas of practical art already selected: drawing covers line, shape, tone and can cover texture; painting covers line, shape, tone, colour and can cover texture; sculpture covers shape, form, texture and can cover line and tone.

The only one not covered was the element of pattern. This became a crucial adaptation to the plan, where to fit in pattern? Printmaking had also not found its place in the structure yet was something the art teacher felt must be taught somewhere. One of the earlier decisions was that 3D should not be taught until 2D was secure, so she decided rather than study sculpture at the end of year 7, they could explore printmaking and pattern? Term 3 of year 7 is now fixed as printmaking and pattern.

Practical elements sorted? Well no. Still no idea of what to actually do… but this could wait.

CONSIDERING THEORY

Now there was a logical progression to the curriculum, theory could be hung on it. Once again, professional judgement came into play as, as long as formal elements are covered, everything is fair game.

DECISION TIME AGAIN

- Who to teach?

- What art to expose students to?

- Should works of art be selected in isolation because they link to the practical skill being taught? Or should you choose an artist’s body of work?

- Who do you choose?

How do you choose? The most famous? The most important? The most revered? The most influential? The most appropriate?

At this stage, the art teacher selected an artist who works within both the area and subject being taught. The though process ran something like, who draws lots of still life? Who paints still life and exemplifies use of colour? Who uses still life and printmaking and pattern?

Chronology also became important at this stage. Art is most akin to history as a theoretical subject, so theory should be dealt with in a similar way. Art history studied chronologically makes logical sense. Art only exists because it was shaped by the thing that came before it and the whole of the western art world is completely dependent on and formed by the things that happen before it and around it. This is its Context. It is terribly hard to understand anything outside of its context, and it’s the same in art.

So, thinking about chronology, would the whole of KS3 need to be in chronological order from Y7- Y9? Or just across each year?

Attempting to teach 3 years in chronological order would mean that by the time you were trying to teach painting or colour work in Y9 you might be in the mid C20th chronologically, and would have to use any artist that fitted the time, rather than the best example of an artist for that media. It was most pertinent to use the most appropriate artist for each area and subject being taught, so the KS3 curriculum is chronological within each year, rather than across the three years.

The only year that is not in chronological order is Year 7, for the reason outlined above and due to reasoning about appropriateness. Unquestionably, the most appropriate artists for colour and still life is Van Gogh, but our Year 7s learn about Picasso and cubism first, before anything else we do, as this the epitome of still life studies. Additionally, if you want the outcomes to be obtainable and for all levels of skill, cubism is easily accessible for y7 drawing. Outcomes in cubism do not have to look like the thing they are supposed to be, this gives a sense of achievement to less able students and stops them being put off immediately, it changes the ‘I can’t draw’ mentality to ‘If Picasso is famous, I can do it too.’ This gives the students confidence to attempt more complex subjects, styles and artists later.

In Y9 chronology became an important factor, alongside the opportunity to study in depth the largest number of artists and movements.

Now the plan looks like this:

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 | ||||

| Year 7 | Still life | |||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Printmaking | ||||

| Picasso | Van Gogh | Bawden | ||||

| Year 8 | Portraiture | |||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Sculpture | ||||

| Da Vinci | Gauguin | Emin | ||||

| Year 9 | Art history | |||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Sculpture | ||||

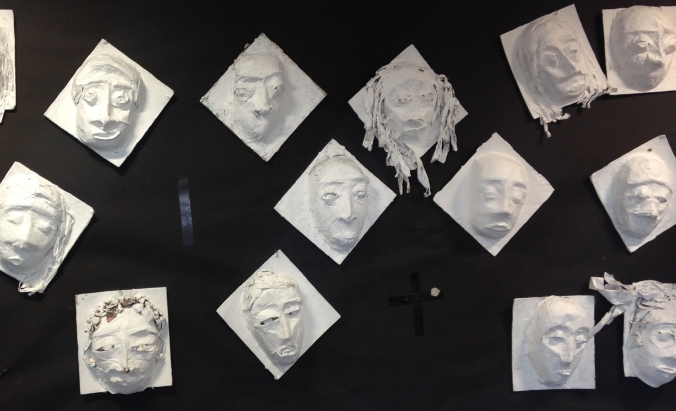

| Van Eyck | Michelangelo | Velazquez | Turner | Moore | Hockney | |

DISCIPLINARY CONSIDERATIONS

Throughout the history of teaching and studying art, there are two main ways of working and learning: working from life (drawing or painting something in front of you) and studying the techniques, style, practices of other artists (copying famous works). Both of these elements must be taught and should have equal importance.

Michelangelo in the Medici sculpture garden in Florence was doing both at the same time – drawing, from life, hugely important examples of classical sculpture that would then go on to influence his work for years to come. Hinterland.

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 | |||||||||

| Year 7 | Still life | ||||||||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Printmaking | |||||||||

| Picasso | Van Gogh | Bawden | |||||||||

| From life | From the artist | From the artist | From life | From life | From the artist | ||||||

| Year 8 | Portraiture | ||||||||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Sculpture | |||||||||

| Da Vinci | Gauguin | Emin | |||||||||

| From life | From the artist | From the artist | From life | From life | |||||||

| Year 9 | Art history | ||||||||||

| Drawing | Painting & colour | Sculpture | |||||||||

| Van Eyck | Michelangelo | Velazquez | Turner | Moore | Hockney | ||||||

| From life & the artist | From life & the artist | From the artist | From life & the artist | From life & the artist | From life & the artist | ||||||

Year 9 is less definable. Students are creating work based on something from life, but in the style of the artist we are looking at, in preparation for GCSE.

CREATIVITY

You may notice a perceived lack of creativity in the KS3 curriculum, in that nothing is drawn from imagination or is an abstract concept to be visually recorded. This is a very deliberate choice.

Let’s, for a moment, think about English and writing. Children learn from the beginning of their education how to form the correct letter shapes. Then how to put different letter shapes together to form words, the structures of grammar; full stops, capital letters, punctuation, joining words. Then words into sentences and sentences in to coherent prose and verse. Now think about art. Sometimes, in art, students are told ‘off you go, draw something’ with no guidance, no structure, no rules. Much art taught in schools is hugely explorative, about developing a sense of self, mark making, draw a thing you’ve seen once or draw from memory. But if you’ve not been given the skills of visual recording or formerly taught visual language you can’t be fluent and will always struggle with putting ideas down. As in English, we first must learn the rules, define the parameters and build our cage, before we have enough skill to master and then bend the rules, finally breaking free from them. This can be saved for KS4. Let the students learn the basics first. Otherwise it’s like trying to fly a supersonic jet before you can walk.

That is the basis of our KS3 art curriculum and the progression from year 7 to 9. Developing in complexity of projects/topics, developing from basic skills to mastery of skills, and of understanding art history and the context and sequencing of art, whilst covering the required formal elements of art and aspects of that will feed into and be built on and developed at KS4.

As well as our art teacher’s own experience of art education, the design of our art curriculum drew on several books: Lectures on Sculpture, John Flaxman (1865), The Handbook of Sculpture, Richard Wesmacott (1864) Art, Eric Gill, (1934), Education through Art, Herbert Read (1958)

Wow. Elstow School is truly lucky to have this expertise helping us develop our primary art curriculum.

LikeLike

Pingback: Curriculum Design: Art. Sallie Stanton and Bedford Free School – teachingandlearningblog

Pingback: Curriculum roundup 2019 | missdcoxblog

Pingback: Curriculum: The why, the what and the when – Catalysing Learning

Pingback: Art curriculum, art history, and cultural capital – Knowledge-Rich Art

This is really insightful! Thank you. Very useful as a Line Manager.

LikeLike